On what 'France' has become...

...and whether or not Europe can survive its far-right obsession

Dear readers,

The country I was born in is no more.

I’ve known that for a while.

And for me, it changed for good in 2015, as we reacted to two horrific terrorist attacks by becoming more afraid, more obsessed with violence, policing and control. Which only led to more fear and more blaming.

Liberty, equality, fraternity… This motto may never have been true, but these days it sounds most of all cruel. A bad joke.

With rise of poverty, a government whose only task is to protect the privileges of its richest mates, France is a shadow of its proclaimed values. Far, far away from the imaginary nation I was told about at school as a child, when, in 1989, we celebrated with glory the 200 years of the first French Revolution, and the choices that came with it: the republic, the right for citizens to vote (for all upper middle class men only back then, which appeared as a progress compared to the aristocracy but was it, really?), and, the most important part (and my favourite), the so-called ‘abolition of privileges’.

At the time, this made my little self so proud.

Now, it makes me laugh… and that laugh turned me into a quasi cynic.

To be honest, yesterday’s results at the European elections didn’t surprise me, but they did appall me, for sure.

I also realised that, all my life, I grew up and evolved with this shadow of the far right about the heads of my living-in-France-Algerian-family. The three of us, my hard-working now late father, my loving mum, and my sister, the now brilliant doctor. And for what? What wrong did we do in this country?

I was one year old when my parents tried to move from a studio flat to a one bedroom (for four…), and when our future neighbours tried to convince the landlord to not let us move in. ‘No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish’ you could read on English windows for long. In France, no one wrote such things, they just murmured ear to ear: ‘No Blacks, no Beurs’.

In 2022, at “my” first presidential elections, Jean-Marie Le Pen and his Front National made it to the second round, beating a socialist, Lionel Jospin, and facing our famous former Paris mayor and long-term president, Jacques Chirac.

It is hard to explain how it felt then, how it feels now.

Don’t get me wrong, many French people are anti-fascist, though less and less, visibly... Many of my French friends also grew up marching against the far right, the FN and Le Pen’s tribe. But THEY could not be kicked out of THEIR country. We could be. They were not the source of the fascists’ hatred, we were.

It is not an easy conversation in France.

Most people think the far right is a theory. They also think a racist person is a criminal capable of murder against foreigners. Less than that is considered quite normal. And if we read Camus’s Stranger, even “killing an Arab” might not really be a crime…

So, badmouthing an Arab, tolerating discrimination or police brutality, and forbidding people from praying in mosques or wearing their religious outfits, all this is not racist, it’s just “French universalism”… Everyone should be equal, as long as everyone act like the dominant group…

If you want (or have to) understand the state of France more in depth, last year, an important book came out that describes the current state of the country, analyses the origins of these issues, as well as summaries all my worries and a lot of my experiences in the country where I was born, grew up, and now live again, after over ten years abroad.

Fixing France tells it like it is: this country, as idealised as it is by Hollywood or French privileged novelists, as tempting as it can be with its cheeses, wines and country houses (again, for some, not for us…), is on a slippery slope.

Nabila Ramdani summarises all the issue in one place.

Fixing France

How to Repair a Broken Republic

Nabila Ramdani

A French-Algerian journalist’s stark critique of her crisis-ridden country—how does France work, how did it get here, and how can it change?

“Today, a monarchical President Macron shows little interest in democracy, while a far-right party founded by Nazi collaborators threatens to replace him. Segregation, institutionalised rioting, economic injustice, the debasement of women, a monolithic education system, deep-seated racial and religious discrimination, paramilitary policing, terrorism and extremism, and a duplicitous foreign policy all fuel the growing crisis. Yet Ramdani offers real hope: the broken French Republic can, and must, be fixed.”

Here is a brilliant very recent review from the LA Review of Book:

The Trouble with the French Republic: On Two Recent Books About French Colonisation

Extract:

In Fixing France: How to Repair a Broken Republic (2023), Franco-Algerian journalist Nabila Ramdani dissects the many failings of contemporary France, finding the still-warm imprint of the old colonial empire wherever she goes, from the racial inequalities that bedevil its social fabric to the modes of thought that dominate its politics. Ramdani writes with urgency and verve. Though ostensibly a plea for French renewal, her book sometimes reads—with ample justification—like a charge sheet against it.

Read more from here:

I recommended the book to my colleagues at Radio France International in English, and they interviewed her in their podcast:

Podcast: Fixing France, opposing immigration reforms, Françoise Giroud

A critique that highlights the gap between France and its ideals.

Listen here:

As for me, I could write so much more… I should. I will…?

But forgive me for now, I had a long, full-on weekend… week, month, year, if not decade…

I’m still processing all this, and pondering about what’s next.

What is sure is that I don’t want to give more focus to the far right, this is obviously not the solution. The media is already very responsible, giving huge platform to our main fascist parties, normalising them, all day, every day.

Meanwhile, here is what I wrote last summer, when the police killed a 17-year-old boy in the suburbs where I grew up, and most of my old friends avoided calling me to be sure not to talk about it…

‘Nothing can change if we’re in denial’: French-Algerian journalist on the riots that have rocked her hometown

https://inews.co.uk/news/world/french-algerian-journalist-riots-rocked-hometown-2449948

“If French media focus on the anger and the violence, the real issue is that French police, unlike any other force in Europe, are at war with the youth of the “quartiers”. Harassment and discrimination have been denounced for years by many observers, including Human Rights Watch and the United Nations.”

At the time, I thought that what could be a game-changer would be a way force the French police and most French institutions to look at themselves and for once to “actually acknowledge the discrimination, the bullying, the racism.”

For nothing can change at a stage of denial.

And that is the bedrock of fascism, to blame the foreigners, immigrants, the poor, the outcasts.

You can also watch my intervention on Channel 4 News on the ongoing racism in France and why the RN profits from it, here:

And an article on social discrimination…

French weekly Charlie Hebdo sued for defamation by a Muslim school in Valence

The weekly satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo is being sued by a Muslim school in southern France after an article linked it to the Muslim Brotherhood. The magazine's lawyers invoked "its editorial line", and denied libel.

Issued on: 07/12/2023

And a conversation on TRT World:

Why is inequality in France the worst in the West?

On the 27th of June, a 17-year-old French boy of Moroccan and Algerian descent was shot and killed by police in Nanterre, a suburb of Paris. Protests immediately erupted, which later escalated into rioting as demonstrators set cars alight, destroyed bus stops, and shot fireworks at police. The scale of the violence has been blamed on fundamental inequalities across French society. But, is inequality really worse in France than elsewhere?

Guests:

-Lester Holloway, Editor of the The Voice

-Melissa Chemam, French Journalist

-Renaud Foucart, Senior Lecturer in Economics at Lancaster University

North African Syndrome

On France and discriminations, a shared experience is revealing, in this essay penned by a talented writer and beautiful human, who has become a friend.

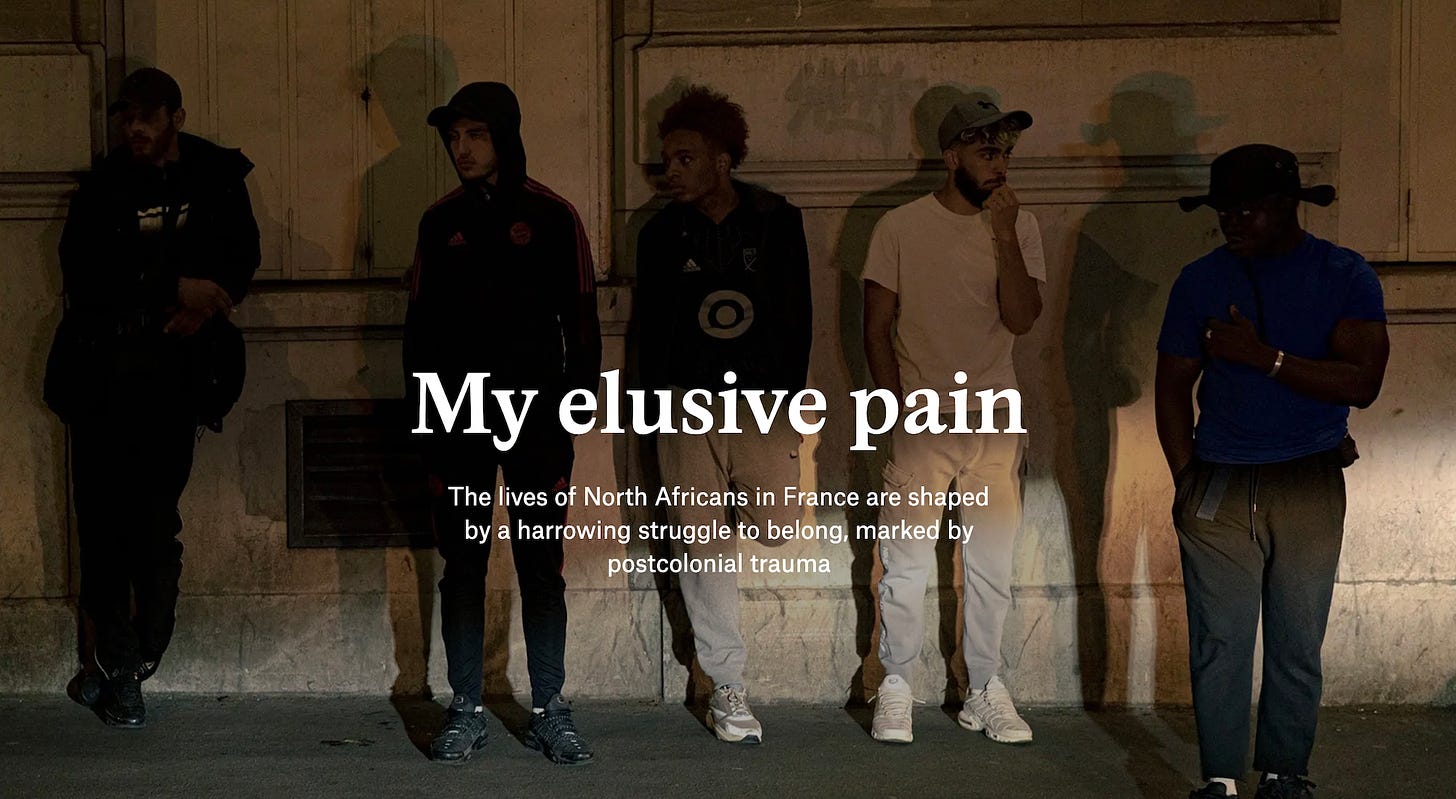

My elusive pain - by Farah Abdessamad

https://aeon.co/essays/living-with-the-enduring-pain-of-postcolonial-trauma

The lives of North Africans in France are shaped by a harrowing struggle to belong, marked by postcolonial trauma

Extract:

I was a sick, curly haired child who would avoid playing outside. Growing up in the west of Paris, I already stood out among my French friends as the kid who was like them but not quite – half white, by way of my mother, and half Arab, by way of my father, which condemned me to a different category of Frenchness. I desperately wanted to blend in, to be a version of what I thought was ‘normal’. But my afflictions made this even harder. They formed a compact repertoire encompassing flu- and cold-like infections that regularly left me coughing until my ribs burned. For a time, I was littered with disfiguring cold sores.

Doctors, friends, even family members dismissed my self-diagnoses, insisting on the familiarly nebulous term of ‘virus’.

(…)

The chronic condition I experienced resembled one that was named long before I was born.

In 1952, the 27-year-old Frantz Fanon had just published his first book, Black Skin, White Masks, his controversial and rejected doctoral thesis on the effects of racism on health. Fanon had been interning at Saint-Alban hospital in southern France when he soon noticed that medical personnel often overlooked and minimised the concern of North African patients. At that time, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia (where my father was born) were either French colonies or protectorates, and these patients were first-generation migrants, men who had crossed the Mediterranean Sea in the aftermath of the Second World War to rebuild metropolitan France.

Life wasn’t easy for them. Most lived in insalubrious working-class estates afforded by their meagre earnings, and occupied the bottom rung of French society. They survived on little more than a deep nostalgia for the home and family they had left behind. And they shared similar symptoms of an unnamed illness. From Fanon’s clinical observations – which would influence his hugely influential book and propel him to join Algeria’s Blida-Joinville psychiatric hospital – he wrote a seminal article exposing a common set of symptoms of what he called the ‘North African syndrome’.

Read more here: https://aeon.co/essays/living-with-the-enduring-pain-of-postcolonial-trauma

Meanwhile, I look far far away for inspiration…

I’m still editing some of the interviews I produced in South Africa for instance, and, though the country today is in crisis, the watershed changes they accomplished in 1994 still amazes me.

Apartheid ended 30 years ago in South Africa, when the African National Congress led by Nelson Mandela was elected to govern the country.

Some of the people who had a major role in this fight were the cultural activists.

Thirty years on, in Johannesburg, I met with the some of the activists who made this fight possible, including jazz legend Sipho Mabuse, in his house in Soweto:

Looking back at cultural resistance in South Africa with Sipho 'Hotstix' Mabuse

I’ll share more soon.

Let’s hope that France and Europe in general find one day their way out of their obsession for purity and racial division too, then we won’t need far right rhetorics or fascist discourses…

Thanks for reading as usual, and if you have a story of inspirational change, feel free to share.

Stay well, stay aware, stay strong,

melissa

-

Melissa Chemam

Journalist & Writer

@ RFI English, New Arab, ART UK, Byline Times...

My blog: https://melissa-on-the-road.blogspot.com/

My website: https://sites.google.com/view/melissachemam

TikTok channel: https://www.tiktok.com/@melissaontheroad

YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCXE4ofFjz0lsRzemjdmFf7w