Dear readers,

I hope this message will find you well.

Some of you may know that I spent a couple of years working from East Africa, between 2010 and 2012. Covering Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia and then Somalia for the BBC World Service’s French-speaking broadcast, I was based in Nairobi and travelled intensely, reporting on the ground on a daily basis. The best situation for a reporter.

I would never have landed in that part of the world if I had not worked in London first, and for the World Service specifically, which is one of the best broadcasters in the world when it comes to African, Asian and South American affairs.

These years changed my life and deeply impacted my way of working in journalism, up to these days.

I cover the whole continent now (what an impossible task by the way…), but I keep a keen eye on East Africa.

Now, two countries are making headlines this autumn, and for good reasons, that impact the whole world, even if it’s not presented that way.

Here are a few reflections.

London's bid to send migrants to Rwanda was stalled when the UK Supreme Court blocked an earlier arrangement as unlawful.

The judges from the UK's Supreme Court last month sided with a lower court decision that the policy was incompatible with Britain's international obligations, notably because Kigali could forcibly return migrants to places where they could face persecution.

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak vowed to persevere with the contentious project by securing the new treaty, vowing to "address concerns" raised in the Supreme Court's ruling.

The UK signed a new migration treaty with Rwanda, after much controversy

Britain and Rwanda signed a new treaty on Tuesday in a bid to revive a controversial proposal by London to transfer migrants to the east African country.

My news story here: https://www.rfi.fr/en/international/20231206-uk-signs-new-migration-treaty-with-rwanda

Why controversy?

Immigration lawyer at Harbottle & Lewis Sarah Gogan thinks that Rwanda's human rights record means the UK government's policy had to be challenged.

"Rwanda is an unsafe country and this is not a quick fix," she said. "You cannot in a matter of weeks or months reform a country and turn it into one with an impartial judiciary and administrative culture."

Yvette Cooper, Labour's home affairs spokeswoman, also dismissed the government's latest plans as another "gimmick".

Oxford's Refugee Studies Centre expert Jeff Crisp analysed that "a sizeable chunk of the Conservative party see the implementation of the Rwanda deal as a means of asserting 'national sovereignty'."

More, as explained by one of Rwanda’s most open voices: opponent Victoire Ingabire:

The new ‘Rwanda deal’ was a shock to Rwandans. We know this is no place for asylum seekers

She writes:

I came to learn about the scheme to transfer UK-based asylum seekers to Rwanda back in April 2022 when it was announced. Incredibly, the arrangement had not been discussed in public before, and even since it was signed there has been minimal debate on it.

I was among the few who publicly disapproved of the scheme, but I could only do so on social media and in foreign publications and channels, as local media would not dare give me the platform.

The policy should be opposed on the basis of the facts. Rwanda is not a free country because political rights are restricted and civil liberties are curbed. Moreover, it remains among the poorest and least developed countries in the world and the most unequal country in the east of Africa region. Anyone transferred to Rwanda will not be offered a real solution because of these constraints. In fact, because of its social and economic conditions, Rwanda also produces refugees.

In the UK, the matter has cynically become a matter of internal politics at this level. For more, see this piece in Al Jazeera:

Rwanda row: PM Sunak, who pledged to ‘stop the boats’, faces crucial test

Sunak’s Conservatives have criticised the plan to deport refugees from the UK to Rwanda as contradicting international law.

In this article, Central Africa expert Phil Clark, who I met 10 years ago in Kenya, said the UK “should be seen as a human rights pariah for its refusal to deal with refugee and asylum claims on its own shores”.

Clark, a professor of international politics at SOAS University of London, added: “However, there has been limited global outcry because many Western states want to emulate the UK’s offshoring approach. Already Denmark and Austria are negotiating similar migration deals with Rwanda. … What the UK is attempting to do with Rwanda, tragically, will soon be the norm for how wealthy countries outsource their refugee responsibilities to poorer states.”

One more argument:

The west’s dumping of migrants on poor countries is a grisly echo of penal transportation

“Imagine that Britain signs a treaty with France agreeing to take its unwanted migrants for cash payment,” he writes, “that France suggests sending lawyers to this country to ensure the British courts treat deportees properly; and that the French national assembly passes a law declaring Britain to be a safe country for its cast-off migrants. What do we suppose would be the response of the Rishi Sunaks and James Cleverlys of this world (not to mention the Suella Bravermans, Robert Jenricks and Matthew Goodwins)?”

Kenan Malik is an Observer columnist.

The most depressing feature of the Rwanda debate, according to him, “has been the degree to which the idea of the mass deportation of asylum seekers has become normalised.”

The controversy was “less about the moral scandal that is the Rwanda policy than about whether it should be even harsher.”

“The logic of performative policymaking is the need continually to ratchet up the rhetoric. If we are serious about questions of sovereignty or of the living standards of British workers, our starting point must be to challenge the government narrative on immigration and to call out the immorality of performative policymaking.”

*

Kenya celebrates 60th year of independence, highlighting the role of Mau Mau rebels

Sixty years ago, Kenya gained independence after 68 years of British rule. It came after a decade of fighting, between 1952 and 1960, notably thanks to the Mau Mau rebellion. This freedom fighters, after decades of controversy on their use of violence, are now celebrated as heroes.

Our story at RFI: https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20231212-kenya-celebrates-60th-year-of-independence-highlighting-the-role-of-mau-mau-rebels

A little bit of colonial history

In in 1884-1885, Africa’s history was changed forever by the Berlin conference, where the great Western powers decided in between them to “share” the continent among themselves to fuel their imperial ambitions.

Colonisation had started way earlier, with France storming North Africa in what is now Algeria as early as 1830.

In 1885, the fate of Kenya fell into the hands of the British, which created the British East African Company, in a similar way companies had been started in India and Nigerian.

In 1895, the company went bankrupt, and the region was placed under the direct authority of the government in London… Under the official name of "British East Africa"

It was soon reincarnated under the new name of "Protectorate and Colony of Kenya", corresponding to the current territory of Kenya and separated from the protectorate of Uganda.

Kenya was colonised by Great Britain between then and 1960.

British settlers came to Kenya for its resources and agreeable climate, forcing indigenous farmers and herders onto infertile land.

They also made many of them work on European-owned farms and plantations.

Historians estimates that the colonial rule created unprecedented ethnic conflict between various groups in a "divide and conquer" campaign, with unfair labour practices, structural racism, and forced resettlement.

Discontent grew progressively, and during the 1950s a sustained rebellion against colonial rule broke, especially the one from the “Mau Mau”, led by Kikuyus, who wished to chase the Europeans out of Africa.

The British launched a war against the Kikuyus, the largest group in the rebellion and in the country, opening detention camps for people suspected of being associated with the Mau Mau, including the elderly and children, and using extreme torture to find information.

Months after the rebellion kicked off in 1952, then British prime minister Winston Churchill declared a state of emergency, paving the way for a brutal repression.

Tens of thousands of people were rounded up and detained without trial in camps where reports of executions, torture and vicious beatings were common.

Over one million Kenyans were forcibly removed from their homes between 1953 and 1960, and put into camps.

Royal grip

The country has always has a special significance for the British royal family, and it is the country where the reign of Queen Elizabeth II began, when she was visiting the country and her father King George VI died in 1952.

More recently, Charles made three previous official visits to Kenya, in 1971, 1978 and 1987, also visiting the country privately.

In 2010, Charles' elder son Prince William also proposed to his long-term girlfriend Kate Middleton while staying in Kenya.

And this year, he travelled as a King of England: King Charles and Queen Camilla undertook a state visit in Kenya from late October to 3 November, to "celebrate the warm relationship between the two countries," according to Buckingham palace.

Yet, among the Kenyan population, the mood sounds keenly different.

"If he is not coming to apologise for the atrocities they did to us then he should not come," 53-year-old accountant John Otieno told AFP.

Many share his view, especially among the descendants of the freedom fighters who opposed British rule.

Buckingham Palace mentioned that the trip would also "acknowledge the more painful aspects of the UK and Kenya's shared history including the Emergency" in 1952-1960, a reference to the fierce rebellions against colonial rule, especially from the Mau Mau.

Charles III didn’t apologise in the end… leaving many disappointed.

He didn’t come back for this 60th anniversary.

Celebrations

Kenya's President William Ruto arrived at the Uhuru Gardens in Nairobi where the country’s 60th 'Jamuhuri Day' celebrations took place.

In Swahili, Jamhuri means “republic” and the holiday officially marks the date when Kenya became an independent country on 12 December 1963.

The Ruto is leading the ceremony held to commemorate the day.

But he stars of the day are the surviving members of the Mau Mau movement, which led the rebellion.

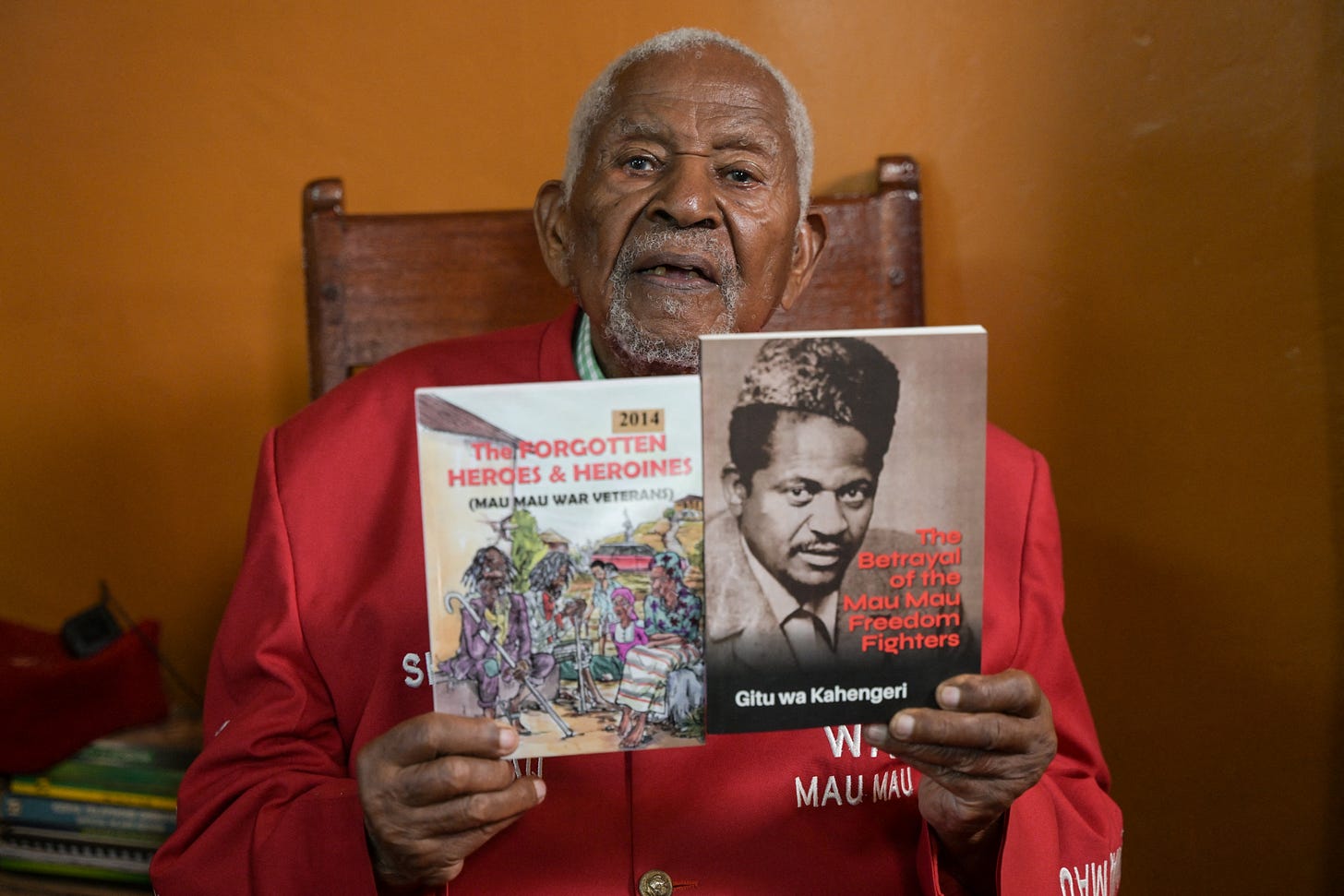

Gitu wa Kahengeri, is one of the rare survivors of the movement. He is now 89, and the secretary general of the Mau Mau War Veterans Association.

"Growing up, I saw how the people around me were treated by the leaders of the colonial administration and I began to wonder how it was possible for a head of the colonial administration to enter the home of a father and start beating us, for no apparent reason, other than being African and living under a colonial government. This is how my political awakening began," he told RFI.

For more, read my article here:

*

Thanks as usual for paying attention.

I wish a great end of the year season, and to a better one…

Best,

melissa

-

Melissa Chemam

Writer and journalist, interested in re-writing cultural narratives

Journalist @ RFI English // Art Writer @ New Arab, ART UK...

Website: https://sites.google.com/view/melissachemam

Newsletter: